Across Australia on the Indian-Pacific

This remarkable woman, with her long skirts and button-up boots, lived in a tent and treated the natives like family. They, in turn, called her Kabbarli, grandmother. She transcribed their legends, did her best to prevent them eating their new-born babies, learned 117 different dialects, buried eleven of her Aboriginal friends in the sand hills with her own hands. Ill health forced her return to the city, where she died in 1951

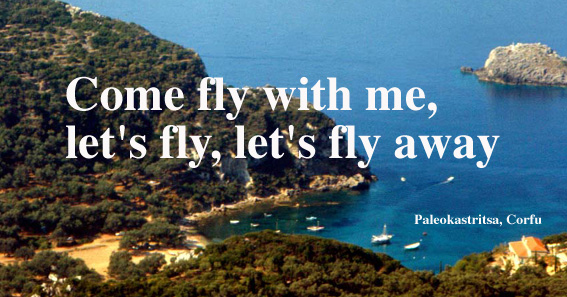

On the logo, an eagle links the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean

On the logo, an eagle links the Indian Ocean and the Pacific OceanIt takes three days, it's occasionally tedious, often fascinating, sometimes even hypnotic. You cross this island continent from one side to the other, from the shores of the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. The aptly named "Indian-Pacific" is one of the world's great trains and the crossing is, surely, one of the world's great journeys.

I made the trip from Perth to Sydney. I have travelled this way before, by air, staring down through wisps of cloud to what looks like a great sheet of wrinkled brown paper below. But I'd always wanted to cross the country by train, getting the look and feel and smell of the place, following in the path of the trail-blazers, many of whom left their bleached bones behind as mute witness to the hostility of the Outback. So by train I came. Along the way, I saw Australia's rugged interior, with its grazing sheep and pale gold pastureland. I saw kangaroos, too, and brilliant native parrots whose wings lit up the sky. But, more than anything else, I remember the wide, flat Nullarbor Plain; this strange, barren heartland is, truly, the Great Australian Loneliness.

Thursday 9pm.

Out here in Perth, capital of Western Australia, the day has been summer-bright, with a breeze whispering in from the sea. We have just boarded the train, a sleek, silver express made up of a dozen carriages, including dining car, lounge/observation car and sleeping cars, which offer single Roomette or double Twinette cabins.

In Perth - and ready to leave

In Perth - and ready to leaveRight on time, we glide out into the gathering dusk. Through the big window in my cabin, I see the lights of Perth flicker past. Soon, I see no lights at all-just a thin orange peel of light on the western horizon. There's a knock on my door, and our steward pokes his head in to greet me with a warm Aussie welcome. "Like a wake-up cuppa in the morning, Sir?" he asks. Then I crawl into bed and sleep.

Friday.

When the tea arrives at 6.30 next morning, we have already travelled over 650 km and rows of neat houses on gum-shaded streets announce our arrival at Kalgoorlie. As we pull into the station, the local radio is chattering on about some boisterous youths caught pouring paint over a revered town statue. Ah, rip-roaring Kalgoorlie, living up to its reputation, I think to myself. But out in the square by the station, all is calm and quiet. There's hardly a soul about. I walk along empty streets, trying to conjure up the past. This town was created by the gold rush at the turn of the century. It grew and prospered, attracting adventurers from all over, including the young Herbert Hoover, who managed a mine a few miles north. At one time, Kalgoorlie's Golden Mile was one of the richest and most rambunctious patches of real estate on earth. Echoes of those days remain in classic architecture, fading facades and rusting mineshafts. The stopover here is short, just thirty minutes. So I make my way back to the train, past the obligatory ANZAC statue, a trooper with fixed bayonet, turned to gilt by the rising sun.

Kalgoorlie: classic Australiana

Kalgoorlie: classic AustralianaKalgoorlie sits on the very edge of a vast, featureless plain called Nullarbor, Latin for "no tree". To leave Kalgoorlie is rather like leaving port for the open sea. Very soon, the trees thin out and disappear, to be replaced by saltbush and spinifex, which covers the orange-red face of the plain like grey foam. This is the sea you now traverse. It stretches for hundreds and hundreds of miles in all directions. You stare out at it for hour after hour, seeing nothing, no sign of life, no animal, not even a bird. Just an occasional watery mirage shimmering on the horizon and the sun, a remorseless white eye in the sky.

Outside, it's baking hot. But the train is air-conditioned; my Roomette is cool and comfortable. In the sun's glare, I draw the shade and look around. This cabin has been well designed: lots of nooks and crannies for storage, small closets to hang things, a folding table, a comfy chair that turns into an equally comfortable bed, reading and night lights, a basin with hot and cold water, a foldaway toilet, ice-water on tap, a speaker for music en route. There's no shower (Twinettes have one) but there's one just down the corridor. Soon, our steward will announce the First Sitting for lunch. There are three separate sittings for each meal; I've chosen the Second Sitting, as it's timed just right for me. And the food aboard is just fine. The lunch that awaits me includes Chicken Soup, Egg and Asparagus Salad, Saute of Beef, Roast Turkey and Peach Melba for dessert. I'll probably order a chilled white Australian wine with my lunch, from the well-stocked bar.

As we continue on across the Nullarbor we pass, from time to time, lonely rows of prefab houses, lined up on the side of the track. These outposts, preposterous and incongruous in this environment, are for the men who must maintain the line. They flash past in an instant - Boonderoo, Mundrabilla, Mungala-and then disappear in a haze of heat. Like desert mirages, there one minute and gone the next.

A big red roo watches the train go by

A big red roo watches the train go byAt 3 o'clock in the afternoon, we reach the start of what is called "the longest straight" - 478 km of track without a single curve, the longest such stretch anywhere. As the sun sets, we reach Cook, where the engines take on more diesel fuel. Cook is the social centre of the Nullarbor, a neat little oasis with school, hospital and dance hall, shaded by peppercorn trees. Then we're off again, the setting sun behind us staining the plain blood red.

Cook: a lonely outpost in the middle of nowhere

Cook: a lonely outpost in the middle of nowhereMuch later, around 11 pm, we pass through Ooldea in the darkness and leave the longest straight behind us. I would have liked to visit this little settlement which stands on the eastern fringes of the plain. It was here, in Ooldea, that the legendary Daisy Bates laboured for years, taking care of the Aborigines who gathered in the sand hills close to the track. Born in Ireland in 1817, this remarkable woman, with her long skirts and button-up boots, lived in a tent and treated the natives like family. They, in turn, called her Kabbarli, grandmother. She transcribed their legends, did her best to prevent them eating their new-born babies, learned 117 different dialects, buried eleven of her Aboriginal friends in the sand hills with her own hands. Ill health forced her return to the city, where she died in 1951. A settlement along the track has been named in her honour.

Daisy Bates

Daisy BatesSaturday.

Breakfast is over now. We crossed the West Australia/South Australia border in the night, made brief morning stopovers in Port Augusta (boring!) and Port Pirie (equally boring- but we did catch a tantalizing glimpse of the blue waters of Spencer Gulf) and now we're racing up into rolling wheat and sheep country. A dusty yellow haze hangs over the scene. Horses stand quietly in the shade of eucalypts, sheep gather at waterholes, wheatfields ripple in the distance and the galvanized roofs of farm buildings flash like mirrors in the sun.

Rural Australia flashes by

Rural Australia flashes byAs the afternoon wears on, the scene changes again. Now the terrain is rougher, with saltbush, tall grass and mulga scrub. There are plenty of kangaroos about; they stand, motionless, watching the train go by and then hop away. I see emus, too: a stately group of these big ostrich-like birds walks in single file along the dried up bed of a river, giving us disapproving looks as we disturb their promenade. And, every so often, flocks of pink and grey galahs take to the air and wheel above us, their plumage brilliant against the blue sky.

Kangaroos peep out as we pass by

Kangaroos peep out as we pass byWe're in New South Wales now, near the state's western border. At 8 pm we reach Broken Hill, a large mining city. Lead, silver and zinc are mined here and then shipped to the smelters at Port Pirie. It's been a hot day; when I get out and wander about, the night air smells warm and dusty. But we don't linger. Another half hour and we're on our way. I have a last drink up in the bar, talking with fellow passengers-a teacher from Ethiopia and his French wife. Someone is tinkling away on the piano. The barman yawns. It is midnight.

Sunday.

Wheat and sheep country again, with lots of hills casting deep purple shadows. We are having breakfast when we pull into Parkes, a pleasant country town 446 km from Sydney. Just before lunch we reach Bathurst, the oldest settlement west of the Great Dividing Range. I see great stone houses here, standing in wooded estates, I see farmhouses standing atop hills and LandRovers kicking up the dust on side roads. An hour later, the hills become sharper and more timbered. We have reached the foothills of the range and are about to climb into the Blue Mountains for the hour-long descent into Sydney.

The Blue Mountains: blue ridges, as far as the eye can see

The Blue Mountains: blue ridges, as far as the eye can seeThis is a whole different world: crisp air, tall timber, tree-ferns, mountain villages, historic gate houses and bridges built by convict labour, waterfalls that leap off cliffs to disappear into valleys far below and bright red, blue and green parrots that squawk at us from the branches of fruit trees. The Indian-Pacific stops briefly at Lithgow then races over the mountain ridges until it reaches the coastal plain below. With the mountains behind us, we thunder over the Nepean River Bridge, streak and rattle and howl our way through the dry western suburbs and reach Sydney's huge Central terminal at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, on time.

65 hours and 3961 km! It's been quite a trip.