Saturday, January 13, 2007

The Performance That Is Tokyo

I’m sitting on a bullet train, speeding like Superman from Osaka to Tokyo. Villages and towns and cities flash by; I expect to look down and see clouds, on what is more like a jetflight than a train journey. I look up and suddenly Mt Fuji appears , a woodblock print framed by my window. And then, just as suddenly, it is gone. The electronic sign tells me Tokyo is not far away.

What, I ask myself, as the train attendant appears and bows to us, will Tokyo offer after the urban bustle and serene beauty we have already seen in Osaka and Kyoto? Will bigger be better? What was once a small Edo era community has been transformed —Samurai to Sony, haiku to Hitachi— into a teeming metropolis and one of the world’s largest cities.

One of the first things I learn, to my surprise and delight, is the relatively easy access via English signage to Japan’s tourism infrastructure—street signs, subway information, stores and restaurants, hotels—even the television in your room offers English cable channels. This means that a tourist’s greatest fear — being stranded in a city and not being able to order food or get from A to B because of language difficulties—is something you won’t have to worry about, unless you’re in some remote mountain village with a backpack.

I stay at the Park Hotel which is located in a new building in a new development in the Shimbashi district, within walking distance of the Ginza. And I quickly discover the secret of Tokyo’s irresistible appeal: the contrasts you can encounter in a single day. I can think of few other cities offering such memorable moments, such dramatic diversity. Tokyo is great theatre from sun-up to midnight.

My ticket to the theatrical performance that is Tokyo offered me, on a single day, three acts worthy of Grand Opera: the scream of power saws slicing up giant tuna in the city’s waterfront fish market followed by elaborately costumed Shinto ceremonies (and weddings) at Meiji Shrine and later, after dark, the extraordinary computer-generated light show that makes Ginza shopping (and window-shopping) the luxest of the luxe. And there were two intermissions of interest: an excursion to a raucous shopping street choc-a-bloc with people, food and bargains, and later, a skyhigh view of the city transformed by twilight.

It's 9.30am. A light rain is falling. I’m here at Tsukji Fish Market located near the Tsukiji Shijou Station on the Oedo subway line and Tsukiji Station on the Hibiya subway line. Tsukji is the world's biggest fish market—a covered area so vast a country town could fit within its walls. It’s busy, noisy and the salty tang of the sea greets you, envelops you and stays with you long after you leave.

The first great fish market was set up under the shoguns several centuries ago. Local fishermen provided fresh fish which were sold near the Nihonbashi bridge, at a market called uogashi, literally, "fish quay". The market flourished and in the restaurants that sprang up around it, sushi was invented in the 1820s. But after the Great Earthquake of September 1923 destroyed much of the city, it was relocated to the Tsukiji district and the current facilities were completed in 1935. They have been improved and extended ever since.

I didn’t get to see the famous tuna auction (it’s now closed to casual visitors) but I do get to see everything else, as I wander around, carefully avoiding the motorized trolleys, laden with gleaming fish, that come dashing at me from all directions. I squeeze and elbow my way along narrow aisles, getting up close and personal with more than 450 different kinds of fish, some still alive, from tiny silver sardines to massive 300kg tuna. More than 700,000 metric tons of seafood are handled every year in Tokyo, with a total value in excess of 600 billion yen. Tsukiji alone handles over 2000 metric tons of seafood per day. The market opens every morning except Sundays and holidays at 3am with the arrival of fresh and frozen fish by sea, land and air from all over the world. The auctions start about 5am, attended by bidders representing wholesalers who operate stalls within the marketplace, and agents for restaurants, food processing companies and large retailers. 8am to 10am is the best time to visit.

It is 11am. I’m on my way to Meiji Shrine, stopping on the way to see the Imperial Palace—or part of it, from a distance. The palace lies in the centre of a large landscaped area, and at one end there’s a walled moat handsomely decorated with white swans. There’s parkland here, too, with clumps of the twisted pines so familiar in this part of the world. It’s a quiet interlude after the noise of the Fish Market.

But soon it’s time to go on, to Meiji Shrine (Meiji Jingu) dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and his consort, Empress Shoken. They are not buried here, but near Kyoto. In Shinto, it is not uncommon to enshrine the deified spirits of important personalities. Emperor Meiji was the first emperor of modern Japan. He was born in 1852 and ascended to the throne in 1868 at the peak of the Meiji Restoration when power was transferred from the feudal Tokugawa government to the emperor. During the Meiji Period, Japan modernized and westernized herself, joining the world's major powers by the time Emperor Meiji passed away in 1912. The shrine was destroyed by allied bombers in 1945, but was reconstructed in 1958.

I walk through the huge cypress entrance torii (gate) and along a tree-lined avenue. In Shinto, passing under a torii purifies a worshipper’s heart before prayers are made to the kami (gods or spirits). Meiji’s 175 acre park is thickly wooded with thousands of trees donated by people from all over Japan. It is November, so I am especially lucky. The weather is fine now, the sky blue, and the chrysanthemums are in full bloom. On each side of the pathway are covered displays which feature the finest specimens of this classic Japanese flower—spectacular in size and colour and quality. Soon I reach the massive Minami Shinmon (south gate) which is also decorated with chrysanthemums. Beyond it, on the other side of a square, I see at last the classic architecture of the shrine itself.

I have, before this visit, already acquainted myself with Shinto and its shrines. I have already seen some, set in perfect gardens, in Kyoto. Shinto, I have learned, is an animistic religion; its practitioners believe everything in nature is inhabited by a spirit. Shinto teaches that when people die, they become kami and are worshipped as spirits by their children and later, their descendants.

Some visitors I see today have come to worship at the shrine. Etiquette varies, but what you usually observe is a bow, then another bow, a hand clap followed by a second hand clap, a silent prayer and then a final bow. Worship begins, however, with the act of purification, which usually involves the use of water. There is a large stone basin here, on one side of the square, so worshippers can perform ritual cleansing by rinsing their hands and mouths.

On another side of the square, I examine votive plaques hanging on a wooden stand. I can’t read Japanese, of course, but know that these plaques are called ema and have wish messages printed on them. “We would like a child”, “I want to pass my university exam” and hundreds of others, some soulful, some (I’m told) hilarious.

I am doubly lucky! Along with chrysanthemums, November is the month when people bring their three, five, and seven year old children (Shichi Go San) to be blessed by the priest in a simple Shinto ceremony. So along with colourful blossoms, I get to mix with colourfully clad children and their parents. I now join them as they approach the shrine in their elaborate kimonos, climb its steps and enter the building. We line up along a wooden barricade, facing a white-pebbled central courtyard, two priests in flowing white robes join us and the ceremony begins with the waving of a bunch of white paper streamers attached to a stick. It whooshes through the air above our heads and the chanting begins. It’s a simple, quiet, formal ceremony and it doesn’t take long. As we leave, another group is already approaching to receive the blessing. So we file out, pausing along the way to sip proffered sake and make an offering. And then out into the November sunshine...to a wedding!

The bride (in distinctive white makeup) is seated at one side of the square, surrounded by family and friends. She is having her white bridal hat, like a large flower pod, adjusted and then the entire family, along with the formally costumed groom, sit for a photograph. I look around: there’s constant movement in and around the square, children in crimson kimonos, robed priests, wedding parties, tourists like myself... it looks rather like, I think, the colourful ebb and flow activity one sees in a coral reef. Just as I am preparing to take my leave, exhilarated by the experience, a bridal procession forms and slowly snakes its way across the sunlit plaza, single file, bride, priest holding a red bamboo parasol, groom, family and friends...an unforgettable finale to Meiji, Tokyo’s best-loved shrine.

The best time to visit a shrine like Meiji is during a religious festival, or in November, or during the New Year holiday. In late May/June, be sure to see the famous Iris Garden (a separate admission fee is charged). Sundays and Thursdays are good, too, because people often bring their babies to be blessed in a ceremony called miya mairi. Meiji Shrine is located at Yoyogi, Shibuya-ku, and the closest subway station is Harajuku. It’s open daily from sunrise to sunset. Admission is free.

The other shrine in Tokyo that’s worth a visit is Asakusa's Senso-Ji. I was able to see it on another day. When you pass under the giant red lantern, look for groups of people gathered around a giant cauldron, fanning themselves in the thick incense smoke while they pray. Buy a lucky charm here to protect you on your travels, or a set of Buddhist prayer beads to wrap around your wrist. Senso-ji is a special world, a quiet oasis of colour and fragrance in the heart of the big city.

2pm. If Meiji and Asakusa represent Tokyo’s spiritual side, Harajuku and the Ginza are here to celebrate Japan’s economic miracle, its booming economy, its fascinating gastronomy and its design know-how. It is afternoon now, and I am about to explore the streets and alleyways of Harajuku—Takeshita Street, Meiji Dori Avenue and Omotesando Dori Avenue. I don’t have to go far. The area sits opposite the Meiji Shrine park. Takeshita Street (Takeshita Dori Exit of Harajuku Station) best exemplifies what this offbeat and fascinating area is all about. The shops here and close by offer an eclectic mix of fashion items and accessories reflecting the Japanese idea of what’s cute and cool, with lots of sugar-sweet Lolitas, rebellious Punk and American Hip-Hop thrown in for good measure. When I arrive, Takeshita Street, a wide alley more than a street, is crammed with customers, window-shoppers and young people just there to be seen. It’s as if a fancy dress party is in full swing. Lots of wild, wild hair—red, white-blond, purple, lots of crazy make-up (on both the men and women) and lots of wilder outfits. This mass of outré humanity, most under the age of 25, moves up and down the street as one. I looked for street performers, but they’re mostly here on Sundays, I’m told.

But my day is not over yet: time to head for the Roppongi Hills complex and Mori Tower’s skyhigh observation deck—for a view of the city as day ends and evening begins. Mori Tower includes an Art Museum, but its Tokyo City View level is what I’m here for, 250 metres above the city and offering a 360 degree view of the metropolis. By subway, you can access Roppongi Hills (yes, the name is confusing - I thought I had to go outside the city to some rural hill area) at Roppongi Station (Hibiya Line). To get into Mori Tower, there’s an admission fee of Y1500 for adults, less for children.

The Observation Deck, served by swift and silent elevators has high curved windows, and the vista is spectacular. I walk slowly around as the sun sets and dusk transforms the city. I leave as the lights of Tokyo come twinkling on, for tonight I am going to Kabukicho in Shinjuku and later to the Ginza, where lighting turns night into day.

8pm. Kabukicho! Could there be greater contrast to the Shinto serenity I saw this morning? Here in this razzle-dazzle entertainment area in the heart of the city, giant neon theatrics overwhelm me. It’s like being in the middle of a crowded disco dance floor—noise, strobes, lasers, music, video, smoke, karaoke, irrepressible joie de vivre. It’s all here—plus great eating— with pulsing percussion provided by the rumble of passing overhead subway cars. In a word: wow!

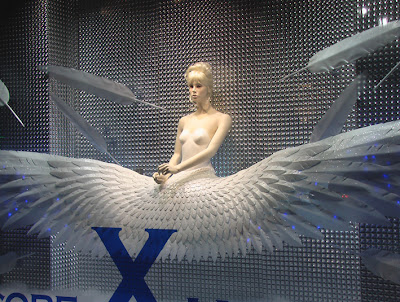

But if Kabukicho brings the performance to a close, it’s the Ginza that provides the curtain call, the standing ovation. It’s now 9pm or thereabouts as I walk slowly along the wide shopping street that’s known around the world. There are people here, but it doesn’t feel crowded. On the Ginza, lighting has been raised to an art form, as digital dreamscapes transform buildings—Chanel’s new mega-store, for example, has 70,000 LEDs to dress up up the entire façade with 7-storey high fashion shows—and window displays echo that dream. During the day, the Ginza is a shopping paradise, if your chequebook can stand the prices—Hello Harry Winston! But at night, the commercial imperative seems to disappear as the lights come on. So it’s here, on the Ginza, my day in Tokyo ends. The curtain falls and the actors depart— except for the lone sax player I see tootling for money outside Tiffany. He is playing Isn’t it Romantic. And it is.

Yokoso! Welcome! to Japan! For more information about Japan, go here.

Here are the sights and sounds of Tokyo!